Navigating the Housing Maze: Lessons from Burlington's Experiment and Why Cherokee County Should Steer Clear

Buyer Beware: Bernie Sanders (ideas and policies) are creeping into Cherokee County

Recently, I’ve been paying close attention to our local leader’s discussions about establishing Community Land Trusts (CLT) or Land Banks in our area to tackle “affordable housing.” I did some research on CLTs and learned that none other than Bernie Sanders, then mayor of Burlington (Vermont) was responsible for the first CLT in the USA in 1984. What started as a noble idea in Vermont didn’t exactly deliver the prosperity promised, and importing similar policies to Cherokee County could tie our hands more than help our wallets.

Personally, I like Bernie Sanders and would love the opportunity to have a beer or a coffee with him. I think he is an interesting man. Whether you agree with his stance on any political topic, his message hasn’t changed much in decades, and that’s something that I can respect. I am also a Larry David fan… but I tend to look away from government solutions to large, complex problems.

What Many People Think they do…

In the mainstream narrative, Community Land Trusts are hailed as a common sense, local solution to housing woes. The idea is simple: A nonprofit, primarily run by the local municipality or municipalities using tax dollars, owns the land, leases it to homeowners at affordable rates, and caps resale prices to keep units “permanently affordable.” Proponents argue this combats gentrification, empowers low-income families, and stabilizes communities. Bernie Sanders, during his tenure as Burlington’s mayor from 1981 to 1989, championed this model. In 1984, he seeded the Burlington Community Land Trust (now Champlain Housing Trust) with $200,000 from city funds, aiming to make homeownership accessible amid rising costs.

Today, the Champlain Housing Trust manages over 3,000 affordable units across Vermont, and it’s often cited as a success story. Reports from organizations like the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy praise it for preserving affordability in specific properties, even as market prices climb. In Cherokee County, similar proposals are gaining traction. Just this year, in May 2025, Canton’s city council considered a CLT to partner with developers for affordable units, and by July, they voted to move forward. A county-wide housing study even recommended exploring a CLT to renovate homes for lower-income buyers. On the surface, it sounds like a win—especially with Georgia’s housing market heating up amid post-pandemic migration and economic growth.

The History Lesson

Let’s rewind to the 1980s in Burlington. Vermont was grappling with a housing crunch, much like we’re seeing in Cherokee County today. Economic booms, tourism, and demographic shifts were driving up demand. Sanders, fresh off a surprise mayoral win, saw the CLT as a way to fight speculation and keep housing within reach for working folks. The trust bought properties, removed the land from the speculative market, and enforced resale restrictions—typically limiting price increases to 25% of market appreciation plus improvements.

At the time, Vermont’s average home prices were already climbing: From $53,100 in 1980 to $75,800 in 1984. Burlington, in Chittenden County, followed suit with similar pressures from university growth and urban appeal. The CLT launched with fanfare, targeting low- to moderate-income buyers. By the 1990s, it had expanded, but the broader market told a different story.

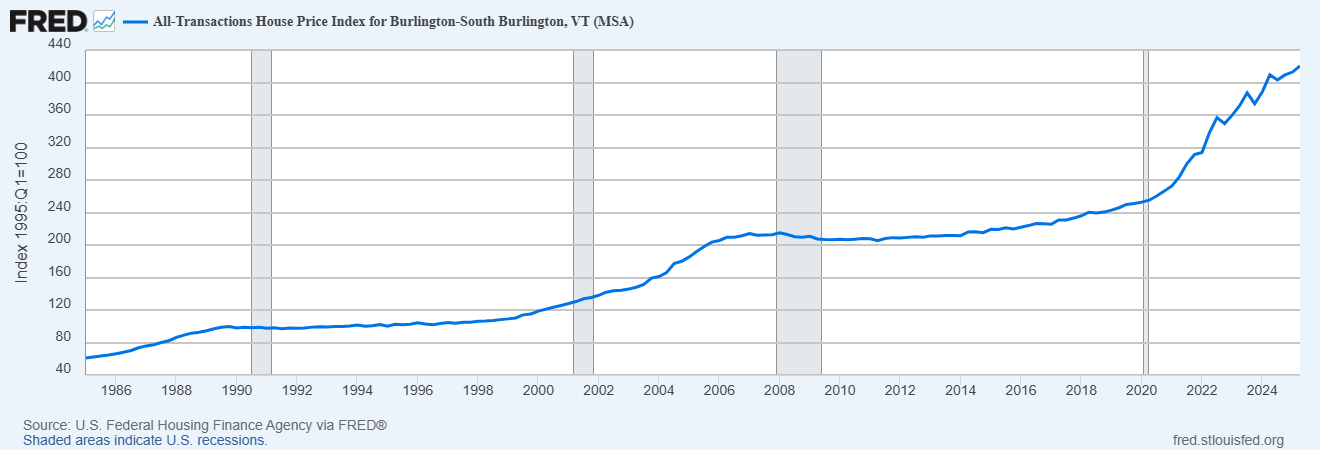

Above is a chart from the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) House Price Index for Burlington-South Burlington MSA, showing the index rising from around 100 in 1995 to over 400 by 2024—indicating prices quadrupled in three decades. Vermont’s median home value also jumped from $42,200 in 1980 to $95,500 in 1990, more than doubling despite the CLT’s efforts.

What the Data Really Shows

Dig deeper, and find the truth. While the CLT created pockets of affordability—about 600 resale-restricted homes by the early 2000s—the overall housing market in Burlington kept inflating. From 1985 to 1990, average prices in Vermont surged 65%, from $73,300 to $121,900. In Chittenden County (Burlington area), prices rose from $84,900 in 1987 to $108,200 in 1990. By 2024, Burlington’s median home value hit $521,486, up dramatically from the 1980s baseline.

Studies show mixed results. A 2023 analysis found CLT purchases can slightly depress nearby home prices (a “negative response”), but the effect is small and doesn’t scale to city-wide affordability. Critics, including urban planning forums, argue it merely shifts costs elsewhere, failing to boost overall supply. In fact, Burlington’s housing crisis persists: As of 2025, vacancy rates hover low, and rents have climbed with prices.

Affordability metrics worsened post-1984. Monthly ownership costs as a share of median income spiked in the late ‘80s, driven by prices outpacing wages. The CLT helped a select few, but for the average Vermonter, homeownership became harder, not easier. As one expert noted, “The trust operates in a market with rising prices and chronic shortages,” underscoring its limitations.

In Cherokee County, we’re seeing parallels. Housing studies highlight supply shortages, with median prices up 5.8% year-over-year in Georgia. But a CLT, as proposed in Canton, risks the same pitfalls—limited impact amid broader market forces.

My unCommon Sense

Government-managed CLTs sound compassionate, but they undermine personal responsibility and market freedom. In Burlington, Sanders’ experiment locked land out of private hands, capping wealth-building for owners (resale limits mean less equity for families). It’s like telling someone with diabetes, “We’ll control your diet for you”—sure, it might stabilize sugars short-term, but it robs you of learning self-management. I’ve thrived by taking personal responsibility over of my health; why not apply that to housing?

The data shows that prices rose anyway because CLTs don’t address root causes like zoning restrictions, permitting delays, or inflation from overregulation. In Vermont, environmental laws added 17% to costs. Here in Cherokee, expanding government power via trusts or land banks (approved August 2025) could distort markets, favor insiders, and hike taxes—remember that 14-mill increase floated in June?

Instead, empower individuals: Cut red tape for builders, incentivize private development with tax credits for affordable units (without strings), and promote financial literacy for buyers. I’ve seen friends increase the chance of homeownership through side hustles— that’s self-reliance. A CLT might “help” a handful, but it entrenches bureaucracy, as critics warn it won’t solve Canton’s challenges and expands city control over property.

Practical solutions?

Streamline zoning to allow more density.

Encourage ADUs (accessory dwelling units) on existing lots.

Partner with private nonprofits sans government oversight. This fosters liberty, choice, and real prosperity—not top-down mandates.

Reflecting on Burlington’s CLT, it’s clear: Good intentions don’t always yield affordable outcomes. Prices soared, affordability dipped, and the market marched on. In Cherokee County, let’s learn from history and choose paths that amplify individual empowerment over collective control.

If you’re wrestling with housing here in Georgia—or just want to chat—drop me a line. Let’s discuss this over coffee or a beer; reach out via email at dan@thrailkill.us or use the Message button below.

Have a good one,

Dan